Teaching to Specific Learning Styles: Does It Really Work?

A Recent Conversation – Does it sound familiar?

I have taught at and been an instructional coach at a career and technical education (“CTE”) center for the last three years. I recently had a conversation with a colleague who teaches our Emergency Medical Technician (“EMT”) course around the idea of teaching to different learning styles, and it got me thinking.

We had finished a day of district-mandated professional development (“PD”) sessions and during one the sessions my colleague attended, the presenter brought up the popular idea of multiple intelligences. Our district, like many in the country, strongly believes in the idea of “personalized learning.” In keeping with this philosophy, we teachers are often told to match our teaching style to the learning styles of our students. To wit, the presenter encouraged the teachers at the PD session to be cognizant of incorporating activities on a regular basis to meet multiple intelligences (represented on the wheel below – looks familiar, right?). Now, my colleague is an effective teacher who already teaches to multiple intelligences. She regularly uses lots of images and interesting metaphors to help students understand how the various body systems function. She gets students up and moving by practicing real-skills on a daily basis. She also provides guided note-taking sheets (with diagrams, etc.) so students can better organize and study the material presented.

Now, my colleague is an effective teacher who already teaches to multiple intelligences. She regularly uses lots of images and interesting metaphors to help students understand how the various body systems function. She gets students up and moving by practicing real-skills on a daily basis. She also provides guided note-taking sheets (with diagrams, etc.) so students can better organize and study the material presented.

Still, she walked away from the PD session frustrated. When I asked the root of her frustration, she said that, though it’s well and good that teachers present curriculum in different ways to engage students, the reality is there is a very difficult exam waiting for her students at the end of her course. To become a certified EMT, students need to pass a computer-adapted multiple choice test of anywhere from 70-110 questions, followed by an intensive skills test. The whole thing takes a full day to complete. While taking the test, students won’t have material presented to them in multiple ways to cater to their preferred learning styles. They have to adapt to succeed. This is true of high stakes tests our students must take all across the country in many subject areas.

What Science Tells Us about Learning Styles

I started doing some research. As it turns out, many experts who study brain science and educational psychology share my colleague’s concerns about the effectiveness of teaching to various learning styles. To begin, as the Poorvu Center for Teaching at Learning at Yale University points out, there are 71 different learning style theories presented in educational literature – far beyond the eight main intelligences referenced above. How can teachers possibly teach to all of these various learning styles? Also, with hundreds of “learning profile” tests out there, it can be hard for students to determine an accurate learning style.

Additionally, even if a student does determine a learning style that works for them, there is little empirical evidence that tailoring instruction to that student’s preferred learning style will result in deeper learning, as discussed in a 2012 article by Doug Rohrer and Harold Paschler. Rohrer and Paschler ended the article with the following suggestion: “Educators should instead focus on developing the most effective and coherent ways to present particular bodies of content, which often involve combining different forms of instruction, such as diagrams and words, in mutually reinforcing ways.”

“Effective and Coherent Ways” to Present Material

So what are the instructional strategies that research has shown to provide the most “bang for their buck,” so to speak? John Hattie of the University of Melbourne, Australia, has been researching this question for years and combined analysis of over 90,000 studies in his book, Visible Learning for Teachers. The table below shows the practices that came out on top time and time again for all different learners.

Teacher clarity implies that teachers consistently make the purpose and goals of instruction clear to students. They should also assist students in setting their own learning goals. Then, teachers must use a combination of direct instruction and classroom discussion to engage students. And this discussion should take multiple forms besides a simple Q & A session (for more ways to discuss, check out Total Participation Techniques by Persida Himmele). Teachers then need to engage students in multiple types of formative assessment to determine how well they understand the material and where they need to go next (for more formative assessment ideas, check out NWEA’s Education Blog). They then must provide students with meaningful and timely feedback so they understand where to go next and ways to get there (for interesting, easy ways to provide feedback, check out this Edutopia article). Finally, students need to engage in metacognition, which could take the form of self-grading or just reflecting on whether they’ve met their learning goals and what process they used.

Piggybacking on this idea of metacognition, Barbara Oakley argues that teaching students the basic neuroscience behind how people learn can also help different learners find more successful ways to study. Oakley is a professor at the University of California San Diego, author of the book Mindshift: Break Through Obstacles to Learning & Discover Your Hidden Potential and instructor of the hugely popular Coursera course by the same name. She argues that teachers can do 5 things to help demystify the learning process, the main one being teaching students the difference between focused and diffused thinking. Focused thinking happens when we first start to learn something new (be it a task or a bit of information). Diffused thinking happens when your mind wanders and mulls over the new task or information; it is where deeper meaning is made. This is why we often need breaks, time and repeated practice to grasp difficult tasks or concepts. We need to allow our brains to go back and forth between focused and diffused thinking. It’s a simple idea with big implications for how students can most effectively study.

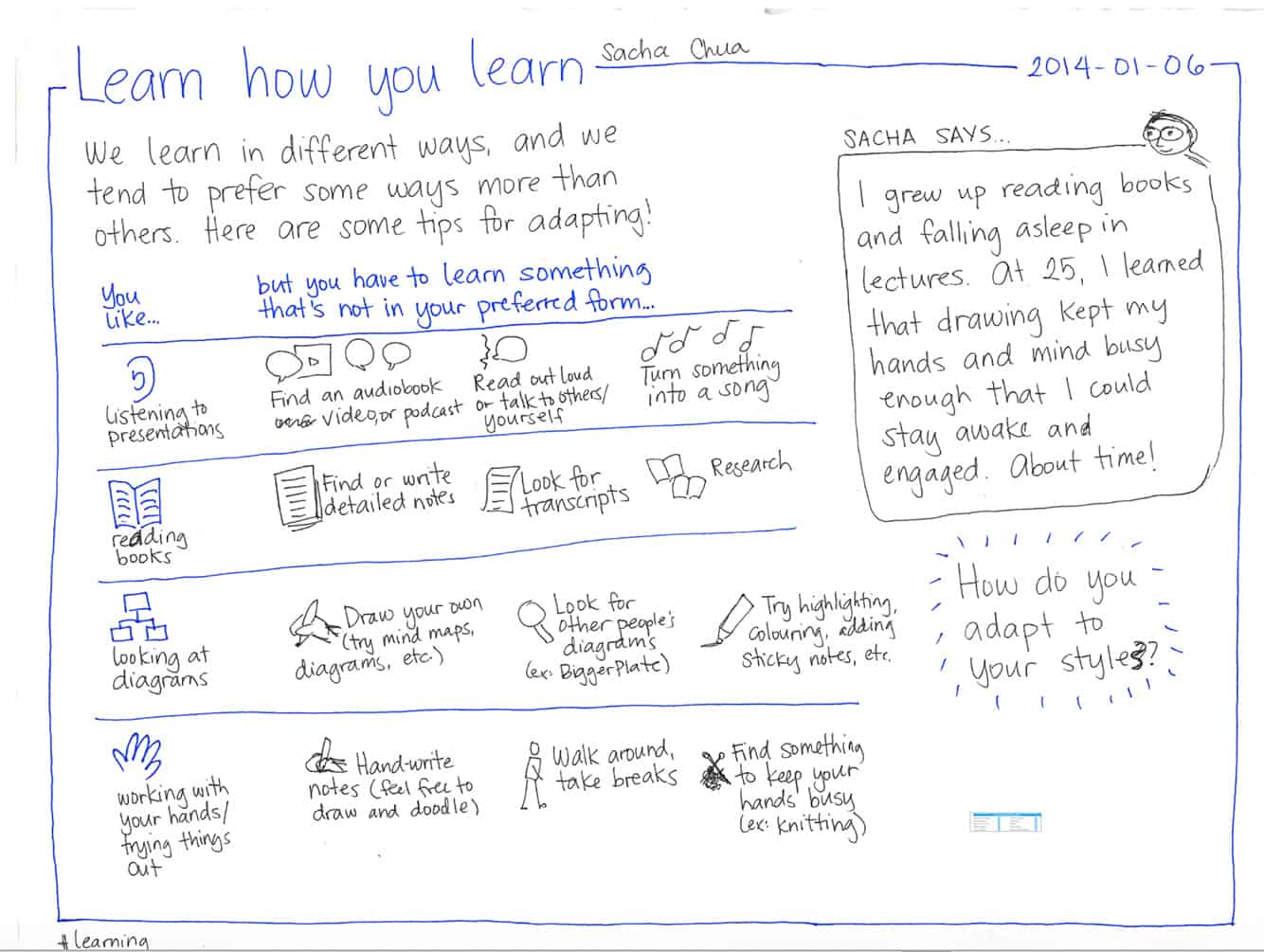

Students Need to Learn How to Adapt & Expand Their Learning

Perhaps the most important reason Barbara Oakley gives for teaching students how people learn is so they will not buy into the idea that they are only one type of learner. This brings us back to the idea of learning styles. When a student thinks they are a Verbal-Linguistic learner and NOT a Logical-Mathematical learner, they can start to put up barriers to their learning. We’ve all heard people say things like “I’m just bad at math” or “I’m a terrible writer.” This kind of thinking can also lead to a lot of test anxiety, which leads back to the frustrations of my EMT instructor colleague previously mentioned. As Oakley said, “We always say ‘follow your passions’ but sometimes that locks people into focusing on what comes easily or what they are already successful at. You can get passionate about — and really good at — many things!”

So, rather than just teaching students in their specific learning style, how about showing them the chart below and helping them determine the methods for adapting that will work for them? Neuroscience tells us we can all learn LOTS of things, if we approach studying in the right way. Why pigeon-hole ourselves unnecessarily to one learning style?

So, here’s what I’m thinking now, in light of all of my recent research: I’m resolving to no longer stress out about including all different learning styles in my lessons. Of course, I will make sure I’m differentiating and modifying for struggling students, but every lesson doesn’t need to have written, visual, kinesthetic, etc. components to it. Instead, I will focus more on having students evaluate how they best learn, develop personal coping strategies for when they aren’t being taught in their optimal way, and set goals for and reflect on their own learning. I will also continue to encourage a growth mindset as Professor Oakley suggested. These are the actions that have been proven to have a bigger impact on student achievement in the long run.